Years ago as part of Lay Ordination I gave a “Way Seeking Mind” talk in which I recalled a longing for a deeper intimacy with the natural world around me: the rocks and trees of the mountains and forests that I loved. But it was the question of birth and death that motivated my entry into practice. They say that when the need arises, your teacher appears, and I was very fortunate that that was the case. Little did I realize at the time how fortunate I was to enter the lineage of Eihei Dogen, and how his teaching responds to both questions.

Dogen, who brought Soto Zen to Japan in the thirteenth century, had a unique way of expressing Dharma in his writings, most of which lay dormant for hundreds of years after his death. As a society evolves, so does its language, creating barriers to understanding what was written long ago. But that is not the only challenge to understanding Dogen’s writings, because he used language as a tool to convey insight that cannot be precisely stated in words alone. He often used poetry to convey his understanding, and created neologisms and used metaphors in a unique manner, often asking us to hold divergent views in mind at the same time thereby forcing the mind to go beyond linear sequential logic. This is true even of his prose writing, and it is unfortunate that even the best translations of his prose are not able to convey the way his words mean.

Early in Dogen’s teaching career, he summarized the core of his teachings in a letter to a student, a letter which he later rewrote and which provided an opening chapter to his masterwork, the Shobogenzo. In Shohaku Okumura’s translation, he says “In seeing color and hearing sound with the body and mind, although we perceive them intimately, the perception is not like reflections in a mirror or the moon in water. When one side is illuminated, the other is dark.” Dogen’s students would have been familiar with the moon as a metaphor for enlightenment and clear reflection as the function of an enlightened mind. To me they also connote passivity. And his students would have been familiar with “illuminated” and “dark” as references to the relative and absolute from teaching poems by Sekito Kisen and Huangzhi. Dogen could have explicated all of this at length, but he preferred a more poetic style that brought these images to mind, but urged the mind to go beyond dualistic understanding of academic philosophy and actually see and hear with the whole body/mind. Even to go beyond what Okumura would call “piddling enlightenment experiences” and actively function completely right here and now with the whole body/mind. Such a felt intimacy is the fruit of actively practicing compassion and insight into interbeing, and sustains our activity. And sometimes this intimacy arises spontaneously, much to our surprise.

As I write this, the entire West Coast is in flames, the air is thick with wildfire smoke from hundreds of fires from the Mexico border to Alaska. I weep over the charred remains of forests I once roamed. People are forced to spend their days inside rather than bask in the glorious radiance of summer weather. Others suffer the consequences of breathing the air that coats their lungs and steals unknown days from their lives. If one can truly feel intimate with one’s surroundings, I wonder how it is possible not to be moved to act in some way to protect the forests, the air one breathes, the lives of people held dear.

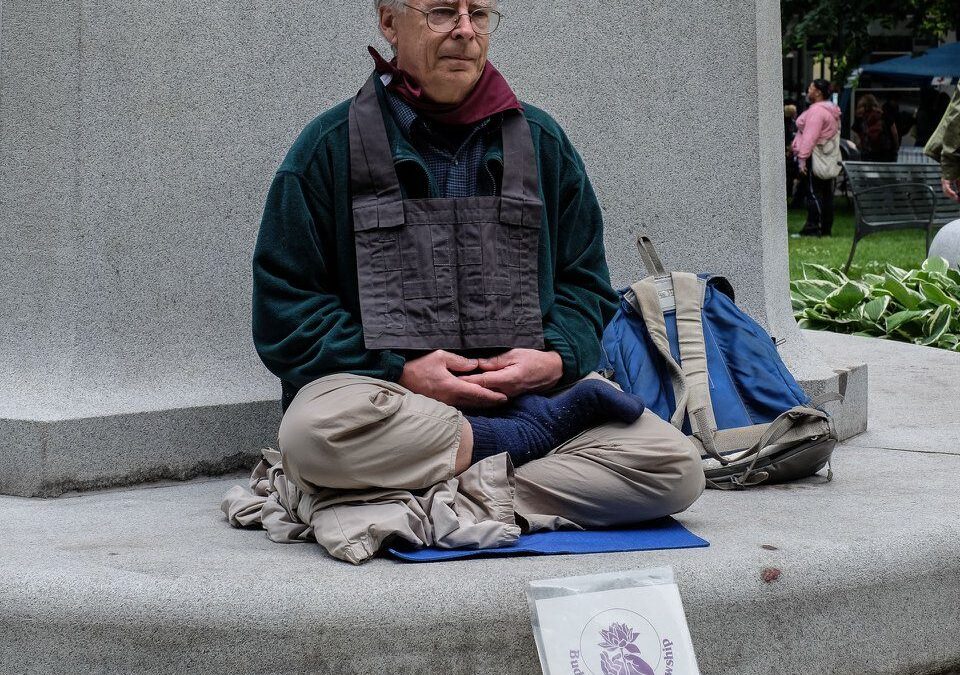

And now institutions we once saw as the bedrock of our freedom are under attack and many have already been reduced to charred remains. Who will speak out in their defense? Fortunately, the Buddhist precepts provide guidance for our activity, recognizing that it is not possible for anyone to live without activity. We are reminded, for example, to use “right speech.” We can speak out in ways that are effective without damaging our own well-being. We can speak without demeaning others or arousing anger within ourselves. “Anger” is a tricky subject: sometimes what we may see as anger can be the force that kick-starts our activity. Passion is the best friend of intimacy, but anger can be poisonous if we attach to that anger and let it grow within where it can reappear in harmful ways. Intimacy is a gift, but it is a fragile gift to be cherished.

And just as one’s understanding will never be the same as any other individual’s (“The marrow is not deeper, the skin is not shallower” was Dogen’s expression), so the path of action one takes will be highly individual, and just as we cannot judge the depths of another’s understanding, so it is equally invalid to judge the depths of another’s commitment to practice and activity. “Life,” “time,” “intimacy,” “activity”: they are all different aspects of the same truth.

An earlier version of this article appeared on the Portland Buddhist Peace Fellowship website