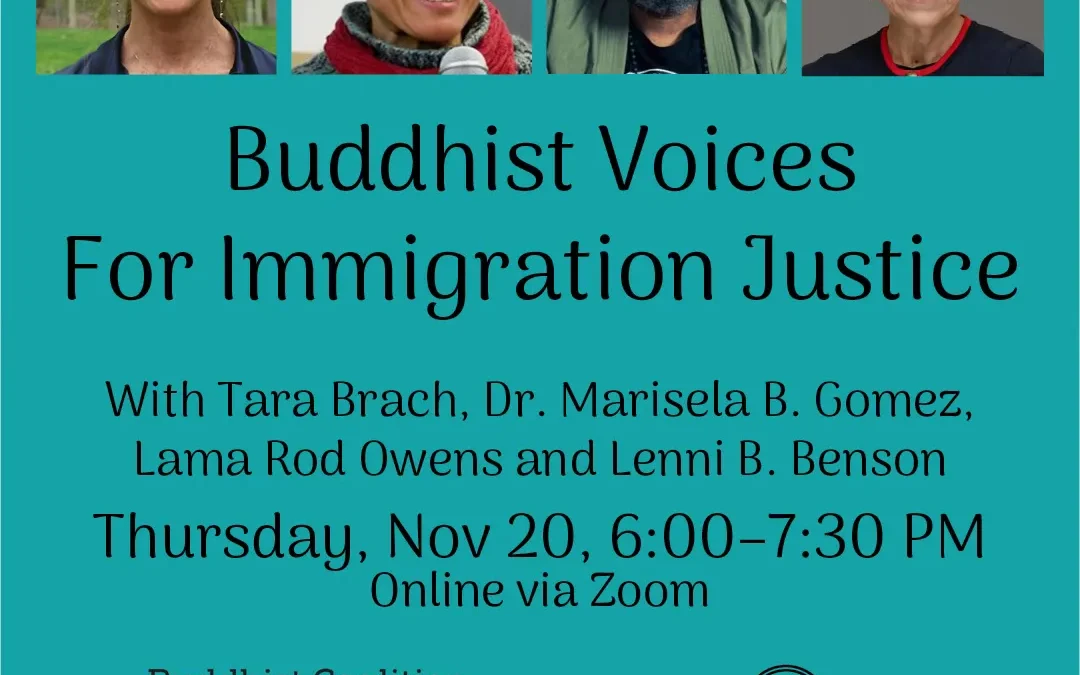

As a member of the coordinating committee for the Buddhist Coalition for Democracy—an organization that supports democracy through methods consistent with Buddhist principles of wisdom, compassion, Right Speech, and nonviolence—I was tasked with writing about our upcoming event on November 20. In partnership with the Insight Meditation Center of Washington, DC, we’re hosting a forum on Buddhism and Immigration featuring leading voices in Buddhism, activism, and law. Together, we’ll explore how Buddhists and non-Buddhists can show up with love and compassion as we witness one of the most significant political disruptions in our history: the hunting and violent deportation of Black and Brown immigrants without due process.

As I grapple with this topic, I find myself circling three things: Gloria Anzaldúa’s book Borderlands/La Frontera, an old video of MNBC Rachel Maddow discovering the imprisonment of immigrant babies, and the question: What does it mean for me as a Buddhist and mindfulness practitioner to make a difference—to live my values and align with the tenets of my practice?

Let’s begin with the Rachel Maddow video.

Witnessing Suffering

In June 2018, MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow broke down on air while reading breaking news about detention facilities holding babies—infants separated from their parents at the southern border. Her voice cracked, tears came, and she had to cut to a commercial. It was a moment of pure, undefended witnessing. The professional armor dropped, and what remained was a human being confronting suffering she could not look away from.

Buddhist practices begin right here: with the willingness to see suffering as it is—not to explain it away or justify it, but to see it. The First Noble Truth asks us to acknowledge dukkha: suffering, unsatisfactoriness, the profound dis-ease woven through existence. But Buddhism also teaches that some create their own suffering, which is maintained and amplified by their choices, policies, and collective actions. And that suffering, we are called to end.

Una Herida Abierta: The Border as Open Wound

I’ve been re-reading Gloria Anzaldúa’s book Borderlands/La Frontera as I organize my current manuscript, Breath, Body, Meets Storytelling: Culturally Centered Mindfulness Practices as Liberation for People of the Global Majority. Anzaldúa writes that the US-Mexico border is “una herida abierta where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.” She wasn’t speaking metaphorically. The border perpetually wounds, never heals, marks a site of unending trauma, violence, and erasure where authorities stop Brown bodies, tear families apart, and render human beings “illegal” simply for existing in space.

But Anzaldúa’s most profound insight wasn’t just about the physical border. It was about what happens psychologically and spiritually to people forced to live in “nepantla”—the in-between space. To exist in nepantla is to belong fully nowhere: not in the country you fled, not in the country that criminalizes your presence. It is to live in perpetual liminality, where home is always elsewhere, safety is always conditional, and your children learn to fear the knock at the door.

This is the violence we must name: not just deportation itself, but the creation of a permanent state of terror. The trauma of raising children who might lose their parents at any moment. The impossibility of planning a future when a policy shift can erase it. The severing of roots, the destruction of communities, the forced exile from the only home many people have ever known.

From “Criminals” to Everyone: The Expansion of Harm

In 2003, when the U.S. government established Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) to target dangerous criminals, threats to public safety, and people who had committed serious crimes, the narrative was clear. The message was simple—we’re going after the bad guys. But that framing was always a lie that made future violence possible, the seed of suffering.

By 2025, under the current administration, we are witnessing the logical conclusion of that lie: mass deportation of anyone without legal status, regardless of their ties to this country, contributions, or whether they’ve committed any crime beyond the civil violation of being undocumented. Parents who’ve lived here for decades. Essential workers who kept us fed during COVID. Young people who know no other home. Families ripped apart not because of what they’ve done, but because of where they were born.

The Second Noble Truth reveals an action: the cause of suffering. These policies are rooted in craving (for ethnic and cultural “purity”), aversion (to those we’ve labeled “other”), and ignorance (of our profound interdependence). We tell ourselves stories—”they’re criminals,” “they’re taking our jobs,” “they don’t belong here”—that allow us to participate in creating nepantla, in keeping the wound open and bleeding.

The First Precept: Do Not Kill

The Buddhist First Precept is often translated simply as “do not kill.” But it extends further than literal murder, asking us not to participate in systems and structures that create the conditions for death, trauma, and the destruction of lives and families.

When we deport a parent, we kill the childhood of the child left behind. When we detain people in conditions that break their spirits, we kill their sense of wholeness. When we create policies that force people to live in perpetual fear, we kill their ability to root, to rest, to become.

This is the violence Anzaldúa named, the suffering Maddow couldn’t contain when confronted with babies in cages, and what the Buddha asked us to see clearly and refuse to participate in.

The Eightfold Path as Response

The Fourth Noble Truth offers us a path: the Eightfold Path, the way to end suffering. It begins with how we live.

Right View asks us to see interdependence clearly. Undocumented hands likely picked the food on our tables. Undocumented labor likely built the roofs over our heads. Our economy, infrastructure, and daily lives are woven with the contributions of people we now seek to remove. To see clearly is to recognize: there is no “us” and “them.” There is only us.

Right Livelihood asks: How do we earn our living? Can we participate in systems that profit from detention centers, surveillance technology, or the machinery of deportation? Can we pay taxes without asking where that money goes? Can we vote for policies that perpetuate nepantla?

Right Speech demands we tell the truth: these are not “illegals” or “aliens.” Black and Brown people are human beings with families. They are neighbors, coworkers, and community members. The language we use either opens the wound wider or begins the work of healing.

Right Action is the most urgent question: What do we do? How do we respond when our government creates the conditions Anzaldúa described, when our policies force human beings into permanent homelessness, when our collective choices keep the wound open and bleeding?

November 20, 2025: A Beginning

On November 20, the Buddhist Coalition for Democracy is hosting a forum on Buddhism and Immigration—not as an abstract theological exercise, but as an urgent moral reckoning. How do we, as practitioners committed to reducing suffering, respond to policies designed to maximize it? How do we apply the precepts and the Eightfold Path in this moment?

These are not questions we can answer on our own. They require collective wisdom, shared practice, and the courage to witness suffering without looking away.

Anzaldúa wrote: “The struggle is inner: Chicano, Indio, American Indian, Mojado, Mexicano, immigrant Latino, Anglo in power, working class Anglo, Black, Asian—our psyches resemble the bordertowns and are populated by the same people.”[1] The border is not only at the Rio Grande. It is in our hearts, in our policies, in our willingness or unwillingness to see each other as fully human.

Buddhism offers us a path: to see suffering clearly, to understand its causes, to know that its end is possible, and to walk the way that leads to liberation—not just for ourselves, but for all beings. The wound is open. The question is whether we will participate in its healing.

Join us on November 20, 6:00 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. EST via Zoom to explore these questions together, to deepen our practice, and to discern the path of Right Action in this moment–because the First Precept is not passive. It is a call.

Register for this event at: https://imcw.org/event/?eventId=1665.

[1]Ruiz, I., & Baca, D. (2017). Decolonial Options and Writing Studies. Composition Studies, 45(2), 226-229,269,272.